John Baptist Lembert was born in New York around 1840, one of several children in a family of German immigrants. Some family members represented their last name as "Lambert". Although John preferred the form "Lembert" in his adult life, even his name was often rendered "Lambert" in books and newspapers. Nothing is known about his formal education in New York. He arrived in California when he was about 28 years old, and worked as a farmer in the San Francisco Bay area. Three years later, he continued farming near Marysville, Yuba County, and then became miner at Buttes, Sierra County. His eldest brother Jacob probably came to California at the same time as John, in 1868, and lived the rest of his life in Mariposa, near Yosemite. This may have been the reason why John also eventually adopted the Yosemite area as his permanent home. In his spare time, John enjoyed creating objects that could best be classified as 'folk arts and crafts'. In 1872, while still a farmer in Marysville, John earned praise for making a smoking pipe out of "cement" and—according to a newspaper note—displaying "considerable artistical skill" {1}.

John moved to the Yosemite region around 1874 or 1875. The attribute "artist" was already attached to his name. In 1877, he painted the flag and carved the flagpole that Anderson and Hutchings would place atop Starr King Mountain. The accompanying text will tell you more about this and other early ascents of Starr King. In 1883, while hiking in the Sierra mountains above Yosemite, Chas Robinson, a San Francisco painter, was surprised to find the interior of Lembert's cabin "ornamented by some amateurish attempts of art, [but] not at all discreditable" {2}.

Shortly after arriving in Yosemite, Lembert discovered the incomparable charm of the lush pasture grounds in the upper country, known as Tuolumne Meadows. A distinctive feature of the Meadows was the bubbling mineral springs, and the name Soda Springs was sometimes used as an alternative name for Tuolumne Meadows. This area was still open Government land and not part of the original Yosemite Grant. Lembert liked to stay in the high mountains for several months every summer, away from the busy and crowded Yosemite Valley. This earned him another frequently used attribute. People started calling him "the hermit". In 1881, a newspaper article titled "The Hermit of the Sierra" described him as "fine looking, well educated and a good talker, yet quite a curiosity. For some unknown reasons he has cut loose from civilization and lives alone in the mountains and seeing a human being only now and then" {3}.

Hutchings described Lembert in 1886 as a "hermit-artist" who makes sketches while his goats graze upon the succulent pastures at the Soda Springs {4}.

Hubert Dyer, a student at Berkeley stopped at Soda Springs in July 1889 on his way to Mt. Lyell. To him, John Lembert, while handsome and quite intellectual, was also a bit of a "peculiar personage... whose mind is filled with the beauties of the scenery and the objects about him. With pathetic simplicity he tells of the dream-pictures of his lonely life..." {5}.

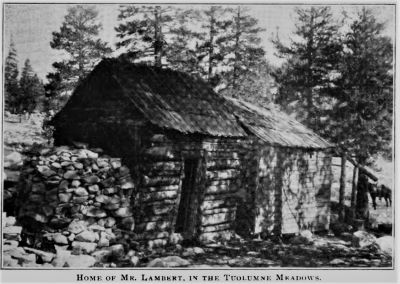

It was there, in the center of Tuolumne Meadows, that in 1885 Lembert staked off a quarter section (160 acres) of grassland north of the Tuolumne River. The springs of carbonated water also became part of his claim. Contrary to what is found in current literature and in National Park documentation, Lembert built his small residential summer cabin near the springs long before he became the homesteader. For example, the botanist John Lemmon spent a night in Lembert's cabin in August 1878 {6}. Today, there is no trace left of Lembert's residential cabin. It was located some 400 feet west of the springs, on a wooded knoll, about where Parsons Memorial Lodge now stands. Sometime between 1904 and 1915 the cabin (or what remained of it) was completely dismantled and removed. Thanks to photographer and writer Helen Lukens Jones, we know at least to some extent what Lembert's dwelling looked like. Her picture of the by then abandoned but still standing cabin was taken in 1904 or earlier {7}.

Another, slightly blurred photo, taken around 1891, probably by George Fiske, also appears to show the same cabin {8}.

Keep in mind that thoe term "Lembert's cabin" is sometimes also used to describe an enclosure that Lembert built of logs around the largest of the soda springs. That structure, nine feet by eleven, not really a place where anyone could live, is now only eight-logs high and roofless, but it still stands {9}.

For some visitors to the Meadows, Lembert's solitary living in this mountain paradise painted a romantic halo around the edges of his aloneness. Others may have found him a bit odd. Many noticed that he always made sure to show only what he wanted to show. For example, no one knew anything about his pre-Yosemite life, not even the basic facts, for he was unwilling to offer and share much information about that. But in general, he was considered a simple, modest man, sociable (although perhaps a little reticent), intelligent, hospitable and kind. It was then a shock for everyone when, in the early spring of 1896, he was found murdered in his winter-season humble adobe near the Merced River, a few miles below Yosemite Valley. Why would anyone want to harm, let alone kill this gentle hermit? However, there was a secret part of his life that only a few of his most trusted confidants knew about. The direct chain of events that would culminate in Lembert's death began in the late fall of 1889, but if we want to understand the whole story, we have to start even earlier.

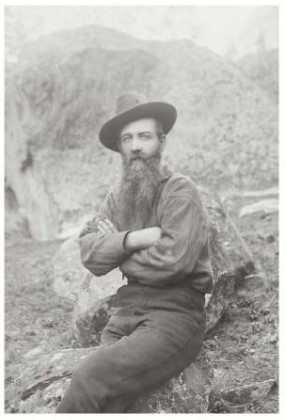

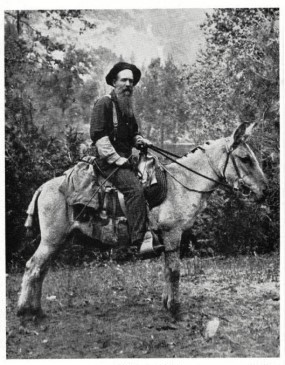

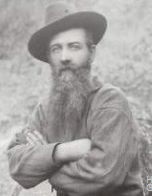

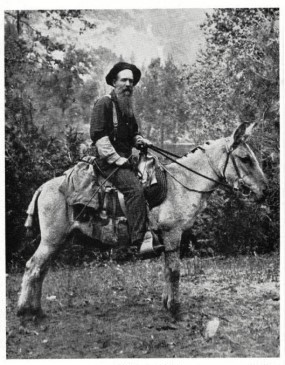

J. B. Lembert, unknown date, probably

around 1880.

In 1885 or earlier, as soon as Lembert fenced off his rich meadow pasture, he acquired a herd of about 150 Angora goats. He probably spent most or all of his savings on that purchase. According to some contemporary estimates, owners of medium size Angora flocks could make a profit of one to two dollars per animal per year. But in the end, everything depended on the market prices of Angora fleece, called mohair. The price of mohair appears to have fluctuated greatly in the mid-1880s. Lembert had to worry about another unpredictable factor, namely the weather: Angoras are not as winter-hardy as other goat breeds, so a suitable winter shelter for the herd in the low foothills was absolutely essential. Therefore, it was crucial to leave the Meadows well before the onset of cold winter storms. Prof. Raymond of the State University at Berkeley once asked Lembert about late fall conditions at Tuolumne Meadows. He replied that he was compelled to leave the meadows and take his flock to their winter quarters as early as October, due to the threat of very cold and sometimes even snowy weather later in the autumn season {10}.

Lembert was therefore fully aware of the possible consequences of staying too long on the summer pastures in the high country. However, even his caution did not help him in the fall of 1889, when a series of extremely cold winter-like storms hit the Sierra mountains early and with a vengeance. There were no official U.S. Signal Service meteorological stations anywhere in the High Sierra or Yosemite Valley at the time, but we can try to reconstruct the events based on weather observations in the adjacent Sierra foothills. At Mariposa, some 50 miles southwest of Tuolumne Meadows, the local clerk, Maurice Newman, carefully recorded the daily conditions and reported the weather patterns in a local newspaper. According to Newman, the first storm of the fall season commenced at Mariposa on the morning of October 7, 1889, and it rained quite heavily most of the day. By that evening, he had measured more than two inches of rain. Generally, this would correspond to about two feet of snow in the high mountains. Lembert may have been in the final stages of preparing to leave Tuolumne Meadows with his goats when that storm hit. A foot or two of snow on the ground would certainly force him to postpone the trip, with the hope that a cold front would pass quickly and the snow would melt. However, in the following days, a newspaper article from Wawona reported that snow remained on the ground and that all scheduled work in the Big Trees area was halted until spring. Similar reports of heavy snowdrifts in the Sierra were published in other California newspapers. Ten days later, on October 17, an even stronger storm made Lembert's situation quite desperate. Almost five inches of rain fell in Mariposa over the next 7 days. The chances of Lembert's flock ever reaching the lower regions now became very slim. In the days that followed, and as the bad weather continued, it must have become clear to Lembert that, barring a miracle, the goats were trapped and doomed. In mid-November, yet another powerful storm dumped 6 inches of rain in Mariposa and many feet of snow in the mountains above Yosemite. It was time for Lembert to leave his flock and try to save himself.

Based on various reports from across California, we can conclude that nothing like this has been observed for many years (or ever), and that the autumn of 1889, with its abundant mountain snow at the start of the season, was a unique meteorological event. The usual routes from Tuolumne Meadows to the foothills became impassable earlier than ever before. By mid-December of that year, a total of nearly 23 inches of rain had fallen in Mariposa since the onset of the storms {11}.

This would correspond to a huge quantity of snow at higher elevations. Indeed, John McKenna reported a previously unheard of amount of snow, a total of 55 feet, accumulated during that winter of 1889/90 at Lake Tahoe {12}.

The heavy losses of several shepherds due to the early arrival of winter were reported in the newspapers, but I found nothing directly connected with Lembert's misfortune. However, a year or two later, when an annual report of the Bureau of Animal Industry was published, it contained the following note on the subject of the mohair industry in the Western states: "Mr. J. B. Lembert, Yosemite Valley, Mariposa County, Cal., was, until recently, the owner of 156 head of Angoras, said to be thoroughbred. His flock, while away from shelter, was overtaken by a snowstorm that continued for twenty-six days. Large number of his animals [actually all!] had to be abandoned to starvation after many weeks of continuous privation" {13}.

Losing his entire investment and thus his livelihood, Lembert had to find other sources of income. The year 1890 must have been extremely difficult for him. In the past, he occasionally guided tourists who arrived at his Soda Springs property to the nearby peaks of Mt. Dana, Mt. Lyell and Mt. Conness. Now, for the first time, he actively offered his services to tourist groups even down in the Valley. He also reportedly bottled and tried to sell water from his soda springs to Yosemite visitors. In the summer of 1890, the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey team of Prof. George Davidson was doing triangulation work in a temporary observatory at the very top of Mount Conness. Davidson reimbursed Lembert for the use of his property as a base camp and pasture. In a report on the work completed in the fiscal year 1890/91, the following statement is found {14}:

"At the lower [Soda Springs] camp Mr. Davidson acknowledged his indebtedness for much local information and many favors to Mr. John Lambert who has a claim there and acted as guide and more." The amount of 'indebtedness' in dollar units was not stated.

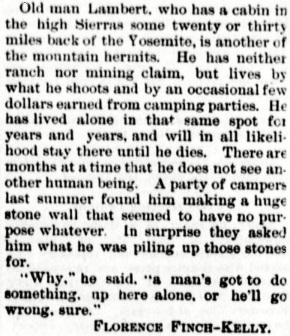

A passage on Lambert from Finch-Kelly's article on

California 'hermits', written in February 1892 and reprinted

in more than 100 newspapers across the U.S.

The year 1890 ended with another terrible setback for Lembert. On October 1, 1890, by an act of the U.S. Congress, all Government land in the highlands around Yosemite Valley was assigned to the newly created Yosemite National Park. Since Lembert had still not received a patent for his homestead, and was too poor to hire a team of lawyers to defend his claim, there was a real possibility that he would now lose control of his Soda Springs property. That winter, as he transitioned into his early fifties, John Lembert probably reached the lowest point of his life.

Then, in 1891, a chance encounter with a scientist from the East Coast changed his fate again. In mid-May of that year, a somewhat eccentric entomologist, Harrison Dyar, came to Yosemite for what turned out to be a four-month visit {15}, {16}.

At first, he stayed in a hotel in the Valley and collected insects from surrounding areas, including from nearby peaks. But in September 1891, Dyar was ready to camp near the headwaters of the Tuolumne River and add a few insects from the high meadows to his collection. Lembert, always eager to learn something new about the flora and fauna of Yosemite {17},

now seized the opportunity to offer his services to Dyar on his camping trip. Dyar's field book indeed shows that they collected some specimens near Soda Springs and near the glaciers of Mt. Lyell between September 17 and 21, 1891 {18}.

Before leaving for Southern California, Dyar asked Lembert to continue collecting rare insects for him. In just a few days, he successfully introduced Lembert to the basics of entomology, including how to collect and observe insects, how to handle samples, and where and how to send them. Lembert will become Dyar's protégé for rearing butterflies and moths (order Lepidoptera). Over the next few years, Lembert sent several hundred specimens to Dyar, but never charged his mentor a penny for those deliveries {19}.

As a sign of gratitude, in 1894 Dyar named a newly identified species of ghost moth after Lembert. He probably also gave Lembert's address to other entomologists and encouraged them to contact Lembert and help him earn something for his skilled work. The word spread and soon people who were engaged in other branches of science started contacting him. For example, botanists from both the U.S. and Canada sought Lembert's help in collecting grasses and other plants from high mountains. Then he attracted the attention of anthropologists from the California State University at Berkeley. At that time, it was still easy to find many artifacts by Native Peoples along the Mono Trail near Tuolumne Meadows, and Lembert was happy to send to Berkeley dozens of the best arrowheads and perhaps some other items found along the Trail. Other anthropologists may have followed suit.

From the time he first met Dyar, John Lembert had steadily gained more and more expertise in his study of insects. He published several of his field notes and commentaries in leading entomological journals from 1892 to 1895. Although publications in scientific journals certainly added to his reputation in the scientific world, such publications did not generate any income. Worse, it became increasingly difficult to bring in new clients interested in buying his plants and insects. By the end of 1893, his income had again become extremely meager. It was probably at that time that he made a terrible decision, which he must have known was unethical, impermissible and completely wrong. It is not clear whether this was his own idea or maybe some of the correspondents encouraged him, but the temptation turned out to be too great. Near his winter cabin, in the Merced River gorge, a few miles below Yosemite Valley, was a burial ground of the local Yosemite Indians, and Lembert was now ready to reach for the relics from that sacred place.

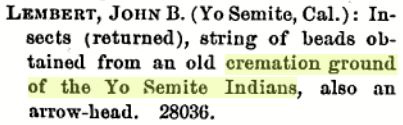

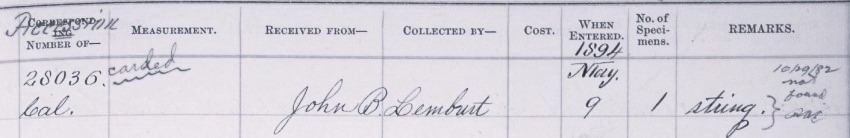

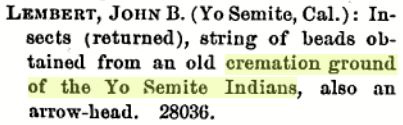

One of his early shipments of objects thus obtained was addressed to the Smithsonian. In their catalog of acquisitions for the fiscal year ending June 1894, we find an item received on May 9, 1894, listed under number 28036: "Insects (returned to sender), a string of beads from an old cremation ground of the Yo Semite Indians, and also an arrowhead". The sender was John B. Lembert of Yo Semite. His insects were rejected.

Acquisition catalogs of other museums and anthropological collections have so far yielded no other entries directly linking Lembert to items looted from Indian burial sites, although there are indications that he disturbed graves more than once. Perhaps it was simply more profitable for him to sell these stolen items directly to Yosemite tourists rather than to institutions.

According to William Colby's 1949 recollection {20},

"Lembert evidently knew the Yosemite Indians quite well, but he apparently fell in their disfavor because he and others[!] had dug up some of their graves in order to get the wampum and other buried relics... Some said it was for motives of robbery that Lembert was killed, and others were sure it was because of the grudge the Indians held against him because he had participated in disturbing the burial sites of their ancestors."

Elizabeth O'Neill also uses the plural 'graves' in her 1983 book on the history of the Tuolumne Meadows region. She wrote {21}, "Lembert did not have the typical Yankee aversion to Indians and lived quite happily among them, gradually learning their customs. But there was a falling out when he went digging up their graves looking for shell money and relics." I cannot tell if her source was the Colby's report (above), or if she used a different independent reference.

But the most detailed and damaging account was written shortly after Lembert's death by 22-year-old Theodore Solomons, who apparently knew Lembert well and gained his trust during their frequent meetings and conversations at Tuolumne Meadows {22}.

Below is the relevant part of Solomons' text. I made only minor changes related to the order and formatting of the paragraphs. Please note that Lembert did not have the opportunity to react to Solomon's chronicle and give us his version of events. It would be best if readers would consider this article to be some kind of literary construction, something between a true story and fiction, and then draw their own conclusions.

The Examiner, San Francisco, May 3, 1896, p. 35.

His Deadly Indian Foe — The Tragic Story of John Lembert

Old John Lembert, naturalist and hermit, had lived in the Tuolumne meadows, near the summit of the Sierra Nevada mountains, during the greater part of each year for something like twenty years. The winters he passed mostly in a little cabin on the Merced just down from Yosemite Valley—the same cabin in which his body was found, two weeks ago. So far as is known, he had no other means than the mere pittance derived from the occasional sale of entomological specimens. But some years ago he began selling specimens of another sort.

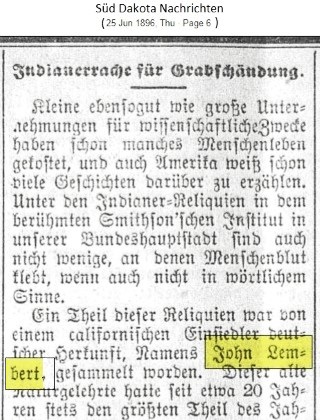

The article "Indianerrache für Grabschändung" (Indian revenge

for grave desecration), based on Solomons' story,

was first printed in Süd Dakota Nachrichten (Sioux Falls).

Near the river, some distance below the great valley that was once all their own, sleep the forefathers of the one-time proud and powerful tribe of Yosemites. Their graves are simply marked, the spot is a secluded one, and few, even among the Indians, approach it. The little group of Yosemites that yet remain revere this lone graveyard as something sacred and tread softly as they pass it by on their way to the pools where the big trout hide in the shadow of the bowlders.

"The old Yosemites," said Lembert to me one evening, in his learned way, "had some funeral customs eminently characteristic of the typical American aborigine. Their obsequies were attended with some little pomp and ceremony, and there were invariably interred with the dead the personal possessions that they most valued or which were esteemed particularly characteristic of them. Thus were preserved many curious relics."

"How do you know?" I asked, innocently. Old Lembert paused. He was not a communicative man. And of course, I did not know the question would be an embarrassing one. "Well, I will tell you," he said, and this was the only confidence I ever got from John Lembert. "I have dug up some of the bodies, stripped them of their beads and trinkets, taken the hatchets and arrows placed beside them and filled up the graves again, just as before. What did I do with them? Oh, I sent them to the Smithsonian, where they have been placed in the splendid museum of anthropology. I understand they had very little or nothing there from the Yosemites."

"And the Indians?" I asked. The old man frowned just perceptibly and stroked his white beard. "They don't like it a bit," he replied, dryly. "I imagined how they would feel about it, so I tried to avoid their seeing me. The only time I felt safe was during wet weather. Then I used to go out with a pick and shovel and dig in the pouring rain. It was dreary work, but I used to keep at it, one grave one time. Then, one afternoon late, as I was busily digging, the heavy rain that had been falling suddenly stopped, and in the stillness that ensued I heard footsteps. As I turned the sound ceased, but I caught a glimpse of an Indian gliding behind a big bowlder. Our eyes met—only for a fraction of a second, but long enough for me to read the expression of his face. I waited, but heard nothing. After a while I approached the rock cautiously, but he was gone. Evidently I had not covered the graves skillfully enough to cheat the eye of an Indian—or perhaps his discovery was one of mere accident."

"It must have been a year after," Lembert continued, "when an old Indian woman murmured a peculiar word as I passed her, yet with a face so impassive I could not imagine what manner of thought she might have had in mind. Some months later another Indian repeated the word as I passed him, sitting near his hut with knees bent under him; and later still—a year perhaps—it was hissed at me as I sauntered along a Yosemite road by a buck who I would swear was the same man that had watched me in the old burial ground. I had the word now, and on inquiry found that it meant what in our language would be best expressed by 'ghoul.'"

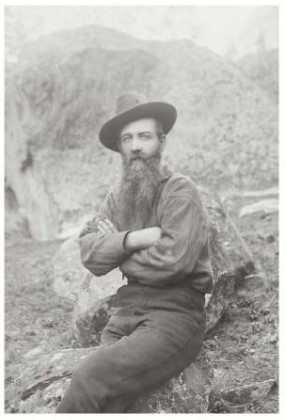

John Lembert, unknown date,

probably in the late 1880s.

Photo Fiske.

"That Indian has kept himself posted on my whereabouts. Occasionally I see him at a distance, looking at me. He dogs me and peers at me from half-hidden places, yet he does so in such a crafty way that I cannot absolutely prove it even to myself. One day, perhaps, he will get me." He laughed lightly at this. "I have doubtless committed an unpardonable crime in his eyes and those of his people, whom he may be delegated to avenge. He meditates killing me, I suppose, and though I were the President of the United States, kill me he will if I give him a chance. Yes, one day the fellow will get me. However, there are some other graves I want to investigate first."

I really think Lembert regarded the horror of the Indians at this violation of sepulcher only as an outgrowth of their superstition or as a kind of idiosyncrasy. How little did he know them. There are but a handful of Indians left in Yosemite and of these not all are of the original stock. Those belonging to the old Yosemite tribe will not leave the valley. They stay, these few men and women, most of them gray-haired and bent, not resembling the stalwart warriors who stole horses and raided like the Doones and fought and died for the possession of their stronghold; but they are Yosemite Indians still, and not Diggers. They reveal their kinship to the old tribe by an occasional flash of the eye and a lighting of the face, but there is added to their native Indian stoicism a certain listlessness of manner which is eloquent of their consciousness of doom and prophetic of the passing of the last sad remains of a once happy people.

Some years have passed since I talked to Lembert. He has probably never told his friends in the Yosemite of his grave-robbing or of his Indian Nemesis. The Indian may have waited all this time, or perhaps the first crime may even have been condoned. But Lembert may then have desecrated those "other graves", and in doing so have sealed his doom. Last fall, as was his wont, when the storm-clouds gathered over the Tuolumne meadows, Lembert packed his books and specimens on his burros and took the trail to and through Yosemite to the little old cabin on the river which had long furnished him a kind of hibernating place. There, two weeks ago the people who winter in the valley went to look for him, found his door padlocked, effected an entrance and saw his body lying on his pallet with a bullet through his temple.

So John Lembert, or "Old Lembert", as he was called, is dead. Next summer the door of his cabin in the Tuolumne meadows will creak on its hinges as usual, but only to the stirring of the breeze. His corral that he worked a whole season to haul to the meadow and erect will be invaded by the passing traveler; and prospectors and sheepherders and the college boys who go to climb Mount Dana will rummage through the old hut and scrawl their names on the walls. There the belated shepherd will shelter himself from the storm, boiling his coffee and frying his mutton in the big fireplace by which for years and years old Lembert pored over his books and studied his insects...

Theo. S. Solomons

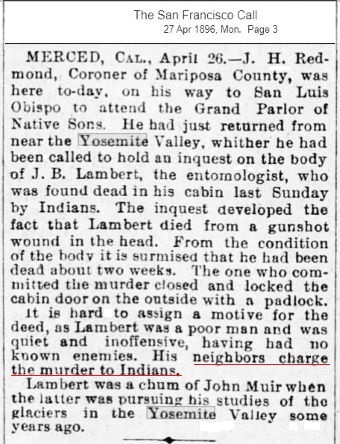

This report clearly left open the question of who commited the crime and why. Many newspaper editors did not like such a conclusion, so they found a legally safe way to blame the Natives. They simply attached to the official Coroner's report claims by alleged (anonymous) neighbors that they blamed Indians for Lembert's murder. The San Francisco Chronicle went even further, reporting that "the impression of the neighbors was that the killing was the work of the Indians, and the result of a quarrel over a squaw"! The Chronicle's special Yosemite correspondent did not feel any pressing need to provide additional details.

Jacob Lembert, John's brother, was living in Mariposa at the time. We can be sure that he wasn't too happy when Solomons' text detailing John's involvement in grave robbing appeared in the San Francisco Examiner in early May. Mariposa's local weekly newspaper, the Gazette, printed—possibly at Jacob's instigation—an unsigned editorial intended to be a rebuttal to the Examiner's story. Unfortunately for Jacob, this turned out to be a total debacle. The editorial must have been put into the paper at the last minute, and there was no time to correct the many typos or—worse—logical errors. Parts of the editorial are almost illegible because the ink did not adhere well to the printing plate. About the "strongest argument" against Solomons' story was a remark about the illustration used in the San Francisco paper (see more about that artist's-impression in the notes for Ref {22}). The editorial stated that some of the allegations contained in the Examiner were about as true as the picture in the article, which did not resemble J. B. Lembert at all. Other "arguments" were even weaker. Find the complete transcript of that editorial in Ref {24}. The Examiner never bothered to respond to this refutation.

For the first two weeks after Lembert's body was found, the story of his death was featured only in California papers. A much wider, national interest was sparked only after the publication of Solomons' article in the San Francisco Examiner. New York's The Sun was one of the first newspapers to carry Solomon's report for East Coast readers in mid-May. However, The Sun changed the headline of the original article to the more derogatory and offensive "The Reds Got Lembert". The headlines of several other papers across the U.S. then followed the Sun's lead.

In early June, the story caught the attention of the editor of a German-language newspaper in South Dakota, who (correctly) assumed that John Lembert's parents had come from Germany. In this gentleman's interpretation of events, Solomon's harsh criticism of the desecration of graves was softened and more tolerance was shown towards Lembert's actions. The German version of the article was first published in the Süd Dakota Nachrichten, Sioux Falls {25}, and then reprinted in other newspapers of German immigrants throughout the Midwest.

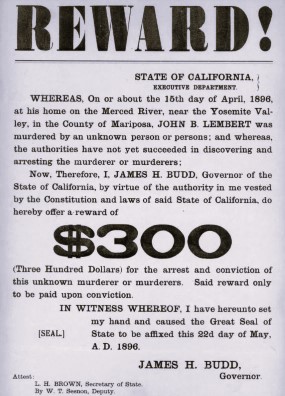

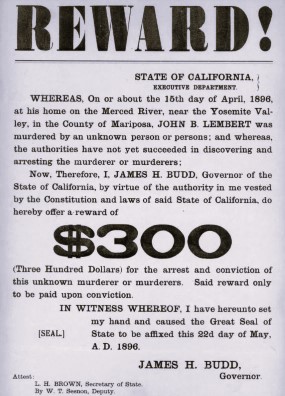

On May 22, 1896, the Governor of California offered $300 for the arrest and conviction of Lembert's unknown murderer(s). There had been no takers.

No one knows exactly who the murderer was or why Lembert was killed. Some people in the Valley spread rumors that Lembert made a lot of money selling all those grasses and butterflies to universities, and that this treasure was hidden somewhere in or near his winter cabin. Margaret Sanborn in her book {26}, tells of a clerk in a general store in the Valley who, on a winter day around 1894, admonished Lembert after the latter allegedly pulled out a roll of bills that might have totaled as much as $1,500 and then peeled off a dollar or two to pay for his purchases. The clerk asked him if he did not consider it risky to carry so much. Lembert was quoted as saying, "Oh, I'm not worried about my neighbors—and I know you are also all right." Lovely story, but I find it difficult to believe that Lembert ever had anything close to that amount of cash. Sanborn discovered this anecdote in a letter written by the 77-years old Laurence Degnan in which he talked about his childhood memories of Yosemite in the mid-1890s. Perhaps the amount of money the clerk originally saw in that roll simply grew larger and larger over time? Our memories sometimes play tricks on us like that.

So, could his death have been inspired by similar rumors? Yes, he could have been an innocent victim of a robbery, but that does not diminish the fact that Lembert was also a desecrator of graves. "He", the avenging Indian, was always on his mind. We actually do not know if that was a real person or just a creation of Lembert's conscience. Regardless, it is easy to imagine that in those final, terror-filled moments of his life, when he realized that someone was forcibly entering his cabin, Lembert's first reaction was: It is He, and He is going to get me this time!

Lembert's body was buried in secrecy. Perhaps an unmarked grave for this hermit-artist-naturalist was the only way to prevent a possible vindictive desecration of his grave. But the story of his life (and death) could have had a completely different ending. Imagine a wealthy insect collector just about to offer him the job of curating his collection; or a university professor who is thinking about hiring him as his assistant in the school's botanical lab. The story could have ended differently if, in a moment of despair, he had not crossed the line he should never have crossed.

As a final irony, another Smithsonian document has a brief comment added next to the entry for acquisition number 28036, the Lembert-contributed "old cremation ground" relics. A hand-scribbled note dated 10/29/1982 indicates that these items can no longer be found and should be considered lost.

Let me conclude this essay with a touching tribute to Lembert written by an anonymous personal friend. It was discovered only recently. (Any guesses as to who the author might have been?)

LEMBERT'S SCIENTIFIC CONTRIBUTIONS

- Articles and notes in the Canadian Entomologist, London, Ontario, Canada:

Exchange.

John B. Lembert

Volume 24, Issue 1, January 1892, n.p.

Colias behrii.—Next June [1892] I expect to collect specimens of this butterfly for sale or exchange. John B. Lembert, Yosemite Valley, Cal.

(Descriptions of Certain Lepidopterous Larvae).

(Harrison G. Dyar)

Volume 25, Issue 6, June 1893, pp. 158-160.

[Dyar in this article directly quotes Lembert's long note on Colias behrii]:

Extract: Concerning the habits of this insect, Mr. Lembert writes:—"July 27th, about nine or ten in the morning of the third day of search, I discovered the food-plant of this hardy little mountaineer. His little queen fluttered into the grass on the meadows at the base of Mt. Gibbs..."

Correspondence:—Argynnis egleis.

J. B. Lembert

Volume 25, Issue 10, October 1893, p. 259.

Extract: Yesterday, August 8th [1893], I went, in an aimless way, to find a new collecting ground. When passing along the brow of a rocky slope, I saw a female A. egleis walking over sticks and burs that were lying on the ground... J. B. Lembert, Summit of the Sierra Nevada, Cal [!]

Food plants of some Californian Lepidoptera.

John B. Lembert

Volume 26, Issue 2, February 1894 , pp. 45-46.

Extract: I have observed the egg laying of the following species of Lepidoptera in the vicinity of the Yosemite Valley...

[It is interesting that Lembert in this article lists his address as J. B. Lembert, Jerseydale, Mariposa Co., California. Jerseydale was a small and remote mining community, 9 miles south-southwest of El Portal.]

Notes on Parnassius clodius.

John B. Lembert

Volume 26, Issue 4, April 1894, p. 101.

Extract: After a journey of ten miles over snow and snowbanks from four to eight feet deep, I arrived in the latter part of June, on my summer and fall collecting ground on the Tuolumne Meadows...

[The address in this and all the following articles is J. B. Lembert, Yo Semite, Cal.]

A Method of Securing Moths' Eggs.

John B. Lembert

Volume 26, Issue 6, June 1894, p. 156.

Extract: A practical way of procuring moths's eggs under my observation last season and the season before...

Glass Tubes as Incubators.

John B. Lembert

Volume 26, Issue 8, August 1894, p. 239.

Extract: On June the 24th, 1893, I was obliged to go to my home in the High Sierras as I had some moth eggs that I wanted to hatch and rear larvae from. It took me three days getting there on account of the deep snow...

Notes on Alypia mariposa.

John B. Lembert

Volume 26, Issue 12, December 1894, pp. 348-350.

Extract: Food plant.—Clarkia elegans, etc. Egg.—Shaped like a white table squash without the scollops...

Preparatory Stages of Euclidia cuspidea, Hübn.

John B. Lembert

Volume 27, Issue 4, April 1895, p. 107.

Extract: Egg: Pea-green colour; round, with deep longitudinal lines from the top to the bottom. Deposited in twos and threes up to us many as eight or nine at one laying before flying away...

Exchange.

John B. Lembert

Volume 28, Issue 4, April 1896, n.p.

[This note was printed at about the time of his death. This was his last contribution to the Canadian Entomologist]:

Wanted.—Specimens of Alypia, Langtonii, Hudsonica, and Brannani, for which I will give California Lepidoptera in exchange. John B. Lembert, Yo Semite, Cal.

- Short field notes

in the Entomological News and Proceedings of the Entomological Section, Philadelphia:

[No title].

J. B. Lembert

Volume 4, April 1893, p. 125.

("I give a new locality for the Lycaena sonorensis, it being in Yosemite on the trail leading to the foot of the Upper Yosemite Falls... I took several during the month of May, 1892...")

[No title].

John B. Lembert

Volume 4, 1893, November 1893, p. 303.

("Among the food-plants of moths, new to science that I have been fortunate in discovering are, of Alypia mariposa, the Clarkia elegans and Godetia williamsonii on the 15th of April 1893... Mr. H. G. Dyar informed me that they were unknown...")

Spider Mimicry.

John B. Lembert

Volume 5, April 1894, pp. 119-120.

("In the middle of October, 1893, I was busily engaged on the banks of the Lyell fork of the Tuolumne River. My attention was attracted to what I supposed was a clear-winged insect that had landed by some mistake in the river...")

Food-Plants.

J. B. Lembert

Volume 6, May 1895, pp. 137-138.

("I have observed the following species.. in Yosemite... during the year 1894...")

Sawdust for Steaming.

B. J. B. Lembert [!]

Volume 6, June 1895, pp. 182-183.

("How I came to use sawdust would be too long a story to tell, but give it, hoping others will be benefited as much as I have been. Mr. Wm. H. Edwards kindly furnished me with a description of his method of steaming insects... but that was not quite the thing for the mid and high Sierras...")

- Reprinted in other journals:

Securing Moth's Eggs. [reprinted from the Canadian Entomologist, June 1894.]

J. B. Lembert

The American Naturalist, Philadelphia, Volume 28, Number 336, December 1894, pp. 1054-1055.

Extract: ...When I take an Arctia ornata and she is ready to lay eggs, the moment she shows signs of being stupefied in the cyanide bottle, I take her out, close the wings over her back, and place her in a paper envelope...

- Brief 'correspondent notes' in the Insect Life, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington

A New Popular Name for the Blood-sucking Cone-nose

[J. B. Lembert]

Volume 5 Number 4 (April 1893), p. 268.

Extract: Mr. J. B. Lembert, a California correspondent, writes us concerning an insect which, from his description, we take to be Conorhinus sanguisuga, and which he states is known in his vicinity as the "Monitor Bug". He says that it is found in beds, and that its bite is severe.

Another "Blood-sucking" Cone-nose.

[John B. Lembert]

Volume 6 Number 1 (November 1893), pp. 52-53.

Extract: We have received, through the kindness of Mr. John B. Lembert, a species of Conorhinus [cone-nose bugs] new to the national collection, and which he has always found in or about beds. The face, hands, and feet of the sleeper are often bitten, causing swelling...

Kerosene Against Mosquitoes.

[John B. Lembert]

Volume 6 Number 4 (May 1894), p. 327.

Extract: Mr. John B. Lembert writes that the miners in the Minaret mining district make a mixture of kerosene and mutton tallow, and smear their "burros" with this ointment. This gives the little animals perfect immunity from the mosquitoes, while without it their heads become simply a crust of dried blood on the outside, so abundant are mosquitoes and horse flies [there].

A Severe Conorhinus Bite.

[J. B. Lembert]

Volume 6 Number 5 (September 1894), p. 378.

Extract: Mr J. B. Lembert writes us that upon the 5th of May [1894] a Conorhinus stung him upon the middle toe while he was in bed. He used saliva to ease the itching sensation but this continued and finally spread over his whole body, including his neck, nose, eyebrows and his scalp. It took several days for him to heal. In a later letter Mr. Lembert states that he has noticed that the Conorhinus is attracted by carrion, and he explains a large number of the poisonous effects of the bite by the mechanical conveyance of putrid animal matter to the wound made by the beak of the insect.

Some Yosemite Moths.

John B. Lembert

Mariposa Gazette, December 16, 1893, p. 2

("One of the notables is Auaphelia Superba, [actually, Annaphila superba], a beautiful tiny little moth... They make their appearance about the first of May in the Yosemite Valley, and are local to that region...")

Correspondence: The "Steel Pen" bug.

John B. Lembert

Mariposa Gazette, February 3, 1894, p. 3.

("On the 27th January, I received a letter from L. O. Howard, assistant Entomologist of the U S. Agricultural Department, enquiring after the origin of the name "Steel Pen" bug, this being the name by which it is known among the miners of Mariposa county. I hope some one will furnish the information, either to me, or to Prof. Howard...")

[A] John B. Lembert

By C. J. S. B. [Charles J. S. Bethune, Editor]

The Canadian Entomologist, London, Ontario, Volume 28, Issue 8, August 1896, pp. 217-218.

Extract: The tidings of his tragic death was a great shock to his many correspondents. The crime is supposed to have been the work of some Indian whom he had offended... He was successful in collecting a number of rare species, and made many careful observations on the life habits of these and other species. The last time I heard from him was in February [1896], when he sent me some specimens and a note on the preparatory stages of Arctia virginalis [a tiger moth]. His untimely death is a loss to entomology, as he was a keen observer and a diligent collector in a little-known locality, and had only just began a work which would have been of great value. He has left neither wife nor child to mourn his departure.

[B] Obituary.

[no author]

Entomological News and Proceedings of the Entomological Section,

Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Volume 7, Number 7, September 1896, p. 224.

Extract: Mr. J. B. Lembert was lately found murdered in his lonely cabin on the Merced River... [Several biographical notes follow, all based on the Solomons' newspaper account in the San Francisco Examiner, {Ref 22}, above]... The theory has been advanced that Lembert was murdered by the Yosemite Indians in revenge for the desecration of their ancient graves while in search for ethnological material for the Smithsonian Institution. He was well known to Eastern entomologists, especially those interested in Lepidoptera, to whom he sent many rare species.

[C] [No title, no author]

Science-Gossip, Illustrated Monthly Record of Nature and Country-Lore, London, U.K.,

Volume 3 (New Series), Number 28, September 1896, p. 108 (the last paragraph on the page).

Extract: The Canadian Entomologist for August contains a sad instance of death whilst collecting rare insects. John B. Lembert for some time past had collected in the Yosemite Park, one of the magnificent public reserves in Western America. Living all alone in the wild mountains of those regions the years round, he was chiefly known by correspondence and the value of his captures. On April 19th last, a passing Indian found his murdered body in the solitary cabin where he dwelt . Pelf could not have tempted his murderer, for Lembert had neither money nor valuables. His death is a great loss to American entomology, for although a collector first, Lembert was a keen observer and recorder of the habits and life-history of insects. His age is supposed to have been fifty-six years, but he leaves no one to mourn for his loss.

[D] Obituary [brief mention]:

Natural Science, Monthly Review of Scientific Progress, London, U.K., Volume 9, Number 58, December 1896, p. 399.

Extract: J. B. Lembert, entomologist, murdered at the Merced River, California.

[E] [No title, no author]

Erythea, Journal of Botany, University of California, Berkeley, Volume 5, Number 1, 31 January 1897, p. 9.

Extract: J. B. Lembert, who has for several years past been a resident naturalist in the Yosemite region of the Sierras, was found dead in his cabin on the Merced River, early last spring. Mr. Lembert was scarcely known personally to Californian botanists, but he had sent some interesting bundles of plants of his region to our University in the last five years. Senecio lemberti Greene, was named in his honor.

[F] Totenschau [=Obituary; brief mention in German]:

Entomologishes Jahrbuch, Jahrgang VII, Leipzig, September 1897, page 247.

Extract: Am Merced River in Californien, fiel durch Mörderhand, der Entomologe J. B. Lembert.

["...fell at the hands of murderers..."]

Callophrys sheridanii lemberti, a beautiful little butterfly named after Lembert.

Photo by Aaron Schusteff from the BugGuide website.

INSECTS AND PLANTS NAMED FOR LEMBERT

I n s e c t s:

- Gazoryctra lembertii (species)

Lightbrown ghost moth that Lembert found along the Lyell Fork. Originally called Hepialus lembertii.

- Chariessa lemberti (species; synonym for Chariessa elegans)

Black beetle with reddish pronotum (section directly behind the head) and legs.

- Callophrys sheridanii lemberti (subspecies; sometimes also called Callophrys lemberti lemberti)

Commonly called Sheridan's hairstreak (or Lembert's green hairstreak), an iridescent green butterfly discovered in the mid-20th century.

P l a n t s:

- Senecio lembertii Greene (species; synonym for Packera pauciflora)

Rare perennial herb from sunflower family, found in the higher Sierra. Also known as Alpine butterweed.

- Amarella lembertii Greene (subspecies; synonym for Gentianella amarella amarella)

Biennial dwarf plant from Gentian family. Produces multiple small flowers in the form of purplish bells.

LEMBERT IN SCIENTIFIC DIRECTORIES/DICTIONARIES

- The Scientist's International Directory, Boston, 1894 and 1896.

- The Naturalists' Directory, Boston, 1895 and 1898.

- A Dictionary of Entomology, David Headrick, CABY Pub, Wallingford, U.K., multiple editions, e.g., as late as in 2011 (see page 801).

An extraordinary achievement for a person who probably had only a basic education in his youth. Note that during the four years covered by this appendix his library/study/laboratory was a small single-room windowless cabin high in the mountains.