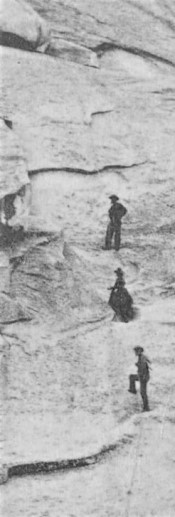

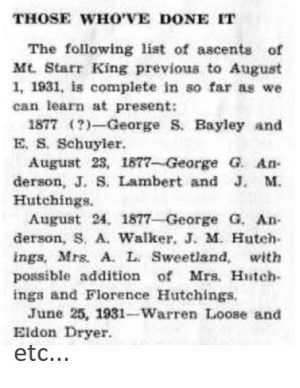

George was the first person to reach the summit of the iconic Half Dome in Yosemite. The date was October 12, 1875.

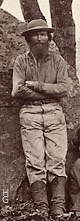

He was one of nine children born to Margaret and David Anderson. In 1851, at the age of 14, he had already left the family home and was working as a cattleman on the farm of a wealthy landowner in nearby Fettercairn. Many years later, when he became famous for his Half Dome adventure, people would describe him as a 'former sailor', or a '(ship) carpenter', or even a 'captain'. He may indeed have briefly engaged in some kind of maritime activity, but so far I have found no evidence of this. British tourist John Wallace, who had the opportunity to speak with George only a few weeks after the first ascent of Half Dome, left us a few additional details about George: "Anderson is fair, blue eyed, bearded, young looking man of about thirty-eight, thorough sailor in appearance, frank and pleasant. He has been seventeen years in California, chiefly mining, but with no great success..." According to Wallace, George Anderson arrived in California about 1858, probably lured by tales of easy gold and quick riches. But George didn't come to California alone. His older brother came with him. In 1858, George would have been 22 years old and his brother Charles about 33. In September 1860, U.S. Census takers found them both in Tuolumne County, near Don Pedro's Bar. They are described as miners without any property, personal or real. In July 1866, George received American citizenship. At that time he owned a mining claim, a water ditch, as well as a house and a piece of land at Indian Bar. By the late 1860s, the gold and copper deposits on that stretch of the Tuolumne River were nearly exhausted, so the Anderson brothers decided it was time to move. [Note: Indian Bar, where the Andersons once had a home, was completely submerged by Don Pedro Reservoir's water in the 1970s]. During the 1870 Census, George and Charles were living quite close to Yosemite, somewhere near Big Oak Flat. Shortly after that census, George moved again, this time to Mariposa County. All the voting lists (aka Great Registers) for that county from 1872 to 1882 list him as "miner, residing at Hite's Cove". In reality he worked as a laborer on much more profitable construction projects in Yosemite Valley, but Hite's Cove may have been his winter home when Yosemite was inaccessible. His Half Dome ascent in 1875 brought him sudden recognition and admiration, at least among Yosemite tourists and residents, and his future prospects were promising.

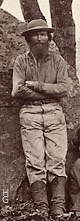

Geo. Anderson

in 1875.

Yosemite Commissioners allowed him to charge one dollar to those tourists who used his rope to climb Half Dome. However, the number of potential climbers was not enough to cover his expenses, let alone to make any profit. In October 1881 one of the Commissioners (M. C. Briggs) offered him a shady contract to build a new wide trail to Snow's Hotel along the north bank of the Merced River. In 1882 and 1883 he devoted himself entirely to this project, but thanks to Mr. Briggs, he was never adequately paid for his efforts. By April 1884, he was penniless. To cover the cost of his meager meals, he gratefully accepted Adolph Sinning's offer to clean and repaint his woodworking shop in the Valley. A severe winter-like storm hit the Valley before he could complete the task, and so he continued to work outside despite the rain and snow. Mr. Sinning urged him to stop immediately, promising him full pay. George replied he had always earned his living and didn't want a charity or handouts from anyone—he would work for it. Not long after, he developed a fever and chills, and was almost forcibly taken to an empty cabin nearby. He lay in bed there for many days without any care or attention. When it was already too late, he was taken to photographer Fiske's house, where he died on May 10 at the age of 48 from acute pneumonia. [The above paragraph is based on a longer account by Charles D. Robinson, a Yosemite artist, who witnessed the events].

George's brother, Charles Anderson, later testified that George had only $2.50 in cash left at the time of his death. The Yosemite Commission reportedly owed him about $1,500. For the next decade, Charles fought the Commission and the State of California for back wages. In 1889, an Assembly Committee of the Legislature concluded that "although Mr. George Anderson, the subject of the disreputable action by the Yosemite Commission has long since gone to his grave in poverty and destitution, mainly consequent upon that wrong, it is hoped that the State will lose no time in repairing, in some degree at least, the wrong done to Mr. Anderson by paying to his heirs the money to which he was justly entitled". However, two successive Governors of California, Waterman and Markham, blocked any such payment, and Charles Anderson never received a penny of the money that belonged to his brother. Charles died in March 1900 at County Hospital in Sonora.

In 1877, James Schuyler spent a night in Anderson's cabin high in the mountains, near the rope route. Next morning Anderson guided him to the summit of Half Dome. Schuyler later recalled: "Anderson is one of the finest specimens of physical manhood I have ever seen. Strong and active like a lion, he is, withal, as modest and unassuming as a maiden—in short one of Nature's noblemen and a gentleman by instinct".

(Find more about George Anderson and early Half Dome ascents in the accompanying article by this author).

{Ref 2, pp. 21-22}.

{Ref 2, pp. 21-22}.

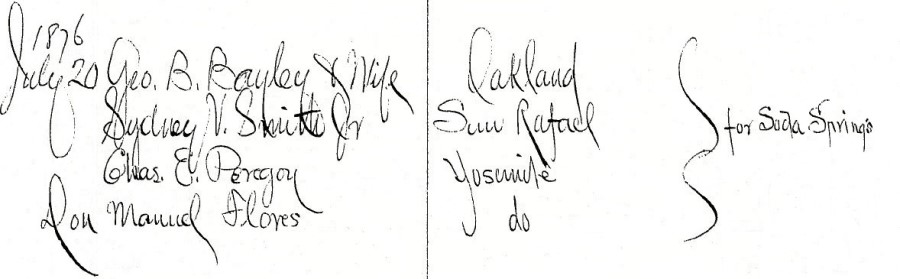

George Bayley's small team makes a brief stop at Snow's on their way from Yosemite Valley to a base camp at Tuolumne Meadows ("Soda Springs"). We learn the names of all team members.

George Bayley's small team makes a brief stop at Snow's on their way from Yosemite Valley to a base camp at Tuolumne Meadows ("Soda Springs"). We learn the names of all team members.